When process becomes punishment: why lessons from Iraq and N. Ireland must not be ignored

Op Banner shows how a legal framework built for accountability can harden into an industry. And Iraq is now following suit. Meanwhile, veterans suffer for service.

There is a tendency in British public life to treat legacy issues as abstract — questions of law, procedure, or historical reckoning.

They are none of these.

They are lived experiences, carried for decades by individuals and families who were sent by the state to serve, only to be left to navigate the consequences alone.

The recent media coverage of the Iraq “lawfare” era is not just about Iraq. Take it as a warning.

At its centre is the case of Sgt Richie Catterall, a British soldier involved in a 2003 firefight in Basra. He fired a single round. The Army cleared him. The Royal Military Police cleared him again. And yet, for more than a decade, he remained trapped in a cycle of reinvestigation — driven not by new evidence, but by shifting legal standards, external litigation, and institutional fear of closure.

Sound familiar?

Eventually, an independent inquiry concluded what had long been established: that Sgt Catterall had acted in self-defence. It also criticised the reliability of key evidence used to prolong the case, including a false or misleading document.

But by then, the damage was done. Years of mental ill-health, family strain, and ultimately a stroke. Vindication arrived late — too late to undo the harm.

This is not accountability. It is attrition.

Why this matters for Operation Banner veterans

The relevance to Northern Ireland is direct and unavoidable.

Operation Banner veterans have long warned that the core danger is a lack of finality. Systems that allow repeated reopening of cases — even after complete investigations — become forms of punishment, not justice.

This is what Iraq demonstrates:

Investigations multiply, not because facts change, but because legal interpretations do

Civil claims, judicial reviews, and public pressure feed one another

Institutions become risk-averse, choosing an endless process over difficult decisions

The individual soldier bears the cost — psychologically, financially, and physically

Northern Ireland and Iraq now sit on the same fault line.

Whatever one thinks of the 2023 Legacy Act, the debate that has followed it has already reopened a familiar door: the idea that more process is always justice, and that closure is somehow suspect. That is not how law works in any other walk of life — and it is not how a serious country treats those it has asked to fight on its behalf.

Accountability is not the issue — proportionality is

Veterans have never argued for immunity from genuine wrongdoing. Serious crimes should be investigated properly and, where evidence exists, prosecuted.

But investigated properly means once — thoroughly, competently, and fairly.

It does not mean:

Repeated trawls through the same evidence

Investigations driven by external litigation strategies

Elderly veterans being pulled back into a process decades later

Families living indefinitely under threat, even after clearance

A system without finality is not morally superior. It is simply cruel.

The deeper lesson

Operation Banner shows how a legal framework built for accountability can harden into an industry. Once it takes hold, it resists closure — not because justice demands it, but because too many people and processes come to depend on perpetual motion.

Iraq did not create that dynamic. It extends it.

This is not about examining the past.

It is about ending the examination once it has been properly done — so responsibility is borne and the living are allowed to move on.

That is not denial.

It is justice completed.

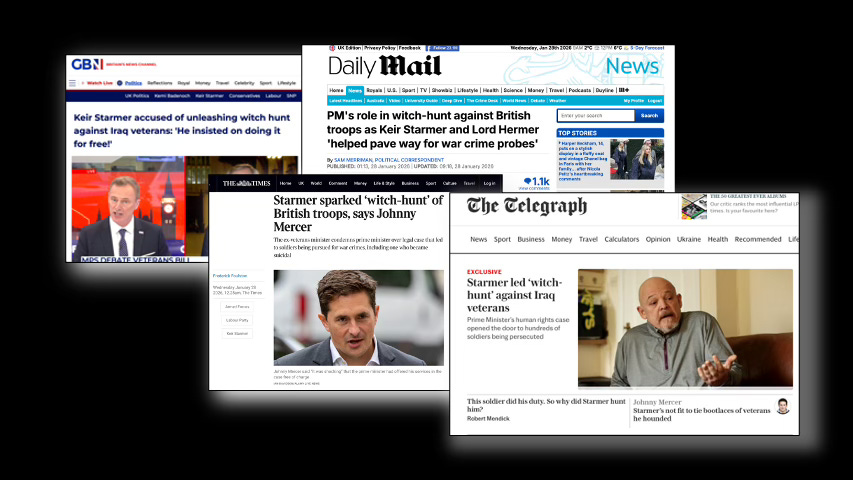

All led by Stammer, whom acted free of charge and not as the next in line barrister. Stammer who now pursues this with his terrorist supporting mate Hermer!

I received the General Service medal and bar for my service in Op Banner it was in recognition of my service to the Crown. It bears the image of Queen Elizabeth II, yet the legal vultures look for ways to tarnish that service to the Crown, it makes ask the question, who governs the legal establishment? I’ve have read accounts when judicial politics have been used to benefit the government. It seems to me that they are not on the side of the Crown. The Nations Armed forces are not political, we leave the political fights up to the Generals and Admirals to fight the cause, sadly I think we have been let down.