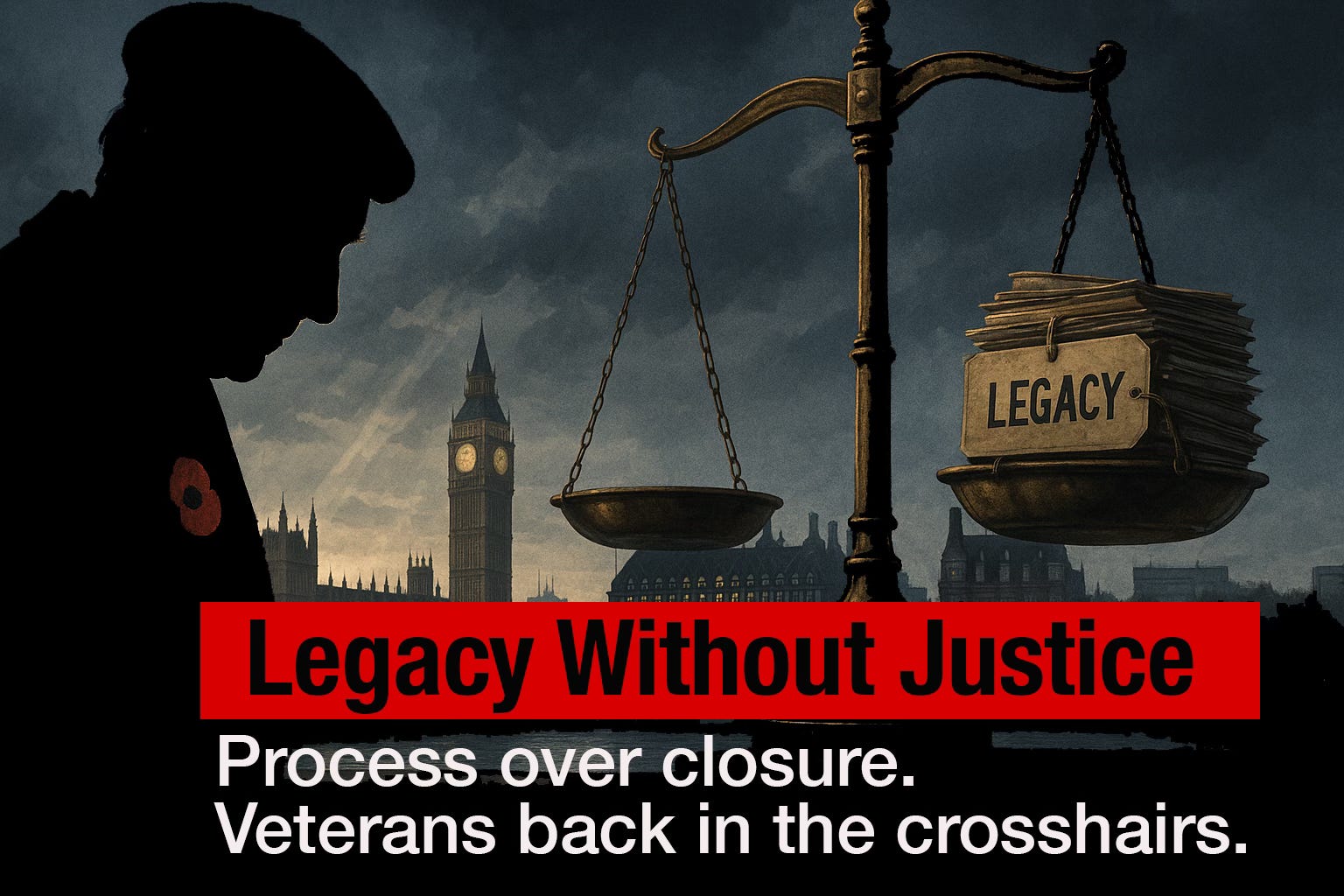

What Yesterday’s Legacy Statement Really Signalled

Seven takeaways from Hilary Benn’s address to Parliament — which raised more questions than provided answers.

A live petition opposing any change that would allow Northern Ireland veterans to be prosecuted for doing their duty during Operation Banner (1969–2007) has now been signed by 208,671 citizens.

Against that backdrop, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Hilary Benn, set out the Government’s new course: repeal and replace the 2023 Legacy Act, via a remedial order now and a new Troubles Bill later. His presentation was confident; the implications are contentious.

Here are the core takeaways with the questions they inevitably raise.

1) Immunity is out; litigation is back in

The Government will remove the 2023 Act’s conditional immunity scheme and lift the prohibition on Troubles-related civil actions. Nine halted inquests are to be restored immediately, with a further 24 sent into a statutory “sift” — explicitly including Loughgall.

Questions:

If prosecutions are, by Benn’s own account, “increasingly remote”, what substantive outcome is expected from reviving litigation-heavy processes now?

How many civil claims are anticipated, and what is the projected cost to the public purse?

2) “Reconciliation” nowhere to be seen

Benn was explicit that the government’s process will not lead to reconciliation — he says it “has to come from within” — so the reformed body will not carry the word. The stated aim is “answers” for families, not reconciliation.

Questions:

If reconciliation is not an objective, what will constitute success — measurable new facts delivered to next of kin within defined timelines, or simply more hearings?

How will the Government report progress in a manner that distinguishes truth-recovery from process for its own sake?

3) Veterans’ “protections” are procedural, not substantive

The protections described (remote evidence, potential anonymity, a duty not to duplicate previous investigations “unless compelling”, MoD-managed contact), were pretty much in place anyway, and only govern how individuals engage, not whether fresh proceedings begin.

Questions:

Who defines “compelling” and by what statutory test, with what independent oversight?

How will duplication be monitored across the commission, coronial system and civil courts?

4) The gateway is political

The statutory “sift” — deciding whether cases go to inquest or into the rebranded commission — is slated for the Solicitor General. MPs queried conflicts and recusals, especially the Attorney General, Lord Richard Hermer’s role. The response was to sidestep the issues with no simple, categorical answer given.

Questions:

Why place a ministerial Law Officer, rather than a named, security-cleared judge applying published tests, in control of the gateway?

What formal recusal regime will apply to Law Officers to avoid the appearance of bias?

5) Irish “co-operation”: promises now, proof later

Dublin has signalled legislation, a dedicated Garda unit and funding. Concrete dates were not offered. Given the historic record on extradition refusals and sanctuary for suspects, any scepticism stems from experience not prejudice.

Questions:

What are the specific Irish legislative milestones and activation dates for the promised unit?

Will regular, public reporting (requests made/fulfilled/refused) evidence co-operation in practice rather than in briefings?

6) The Carltona/Adams knot remains live

Benn said forthcoming legislation would “put beyond doubt” that interim custody orders signed by junior ministers were lawful, and that interim provisions would remain until the new Bill takes effect. Debate continues, however, over whether compensation claims (e.g., arising from the 2020 ruling) are definitively foreclosed.

Questions:

Will the Bill contain explicit, retrospective clarification drafted to withstand challenge?

If not, what exposure remains between the remedial order and Royal Assent?

7) Ends and means: prosecutions “remote”, while process immediate

Benn admitted that prosecutions are “increasingly remote”, but that many families want “answers”. Yet the machinery being revived — inquests, civil suits, a reworked commission — is adversarial by design. The optics are of litigation, not closure.

Questions:

If the goal is illumination rather than conviction, how will the system avoid incentivising lawfare over truth-recovery?

What real safeguards exist for elderly and infirm veterans asked to participate in processes unlikely to culminate in trials?

Then there is the public rationale

The language has shifted over the past few months from the Legacy Act being “unlawful” to it “not meeting obligations”. More to the point, a recent Policy Exchange paper is scathing about the Government’s characterisation of the 2023 Act and the courts’ response to it, stating:

“The present Government’s entirely confused conduct in relation to the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act 2023, with its false claim that provisions of it had been found to be ‘unlawful’ was a policy rationale for making the draft Northern Ireland Legacy Remedial Order clearly manifests this attitude of unthinking (literally thoughtless) compliance.”

Questions:

Will ministers set out, in precise legal terms, what the courts actually decided (and did not decide) on the 2023 Act, so the public can see the real driver for change?

Why proceed by remedial order before publishing the full Bill text and firm delivery timelines in both jurisdictions?

Veterans back to uncertain future

With 208,671 signatories opposing any change that would permit prosecution of those who served during Operation Banner, the Government has chosen a path that reopens inquests and civil actions while conceding prosecutions are unlikely and reconciliation cannot be legislated.

The case now turns on the fine print: dates, definitions, oversight and evidence of reciprocity — not the confidence of the rhetoric.

And, veterans who served their country are again waiting for a kncok on the door.

How utterly disgraceful. This Labour government are just evil. Our soldiers are sent to do the governments bidding and then they turn on them once they are past their usefulness.

As a seasoned veteran. I watch with sadness the way the British Government, is behaving towards our veteran community and indeed, the fallout from the Northern Ireland so-called "Legacy Act!" It's blatantly clear, that moral backbone and fibre is lacking in support of the brave men and women who served and fought, Yes I say fought! Against a Republican Terrorist Network that seeks to undermine British Sovereignty in Northern Ireland. This terrorist organisation, works below the depths of humanity! Slaughtering its own people as well as British combatants, without any regard for human life to further it's own agenda. Instead of them and those that support them being brought to justice, the insanity is, that those who fight for peace, equality and justice, are being penalised and hounded for doing their job, in the most difficult and unpredictable circumstances. To those who are opposing us. They need to know that their illegally crafted words will "Not Win This Battle!" Truth, Humility, Legality and Right bears a solid testimony. To all the service personnel who served. "We serve, We Fight, We Protect the rights of Country King and citizens from the evil ones who pervade our societies!