The Veterans Commissioners and the Legacy Question

The Veterans Commissioners blinked — and veterans noticed.

Two official statements from the Veterans Commissioners for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland — one in July and one in late September — triggered a lively and telling response from veterans and supporters on LinkedIn. Read together, the documents suggest a shift from clear red lines to pragmatic accommodation.

The Commissioners face a difficult choice: defend veterans or accept political compromise.

The veteran community appear to believe the Commissioners have chosen compromise over principle.

From Defiance to Accommodation

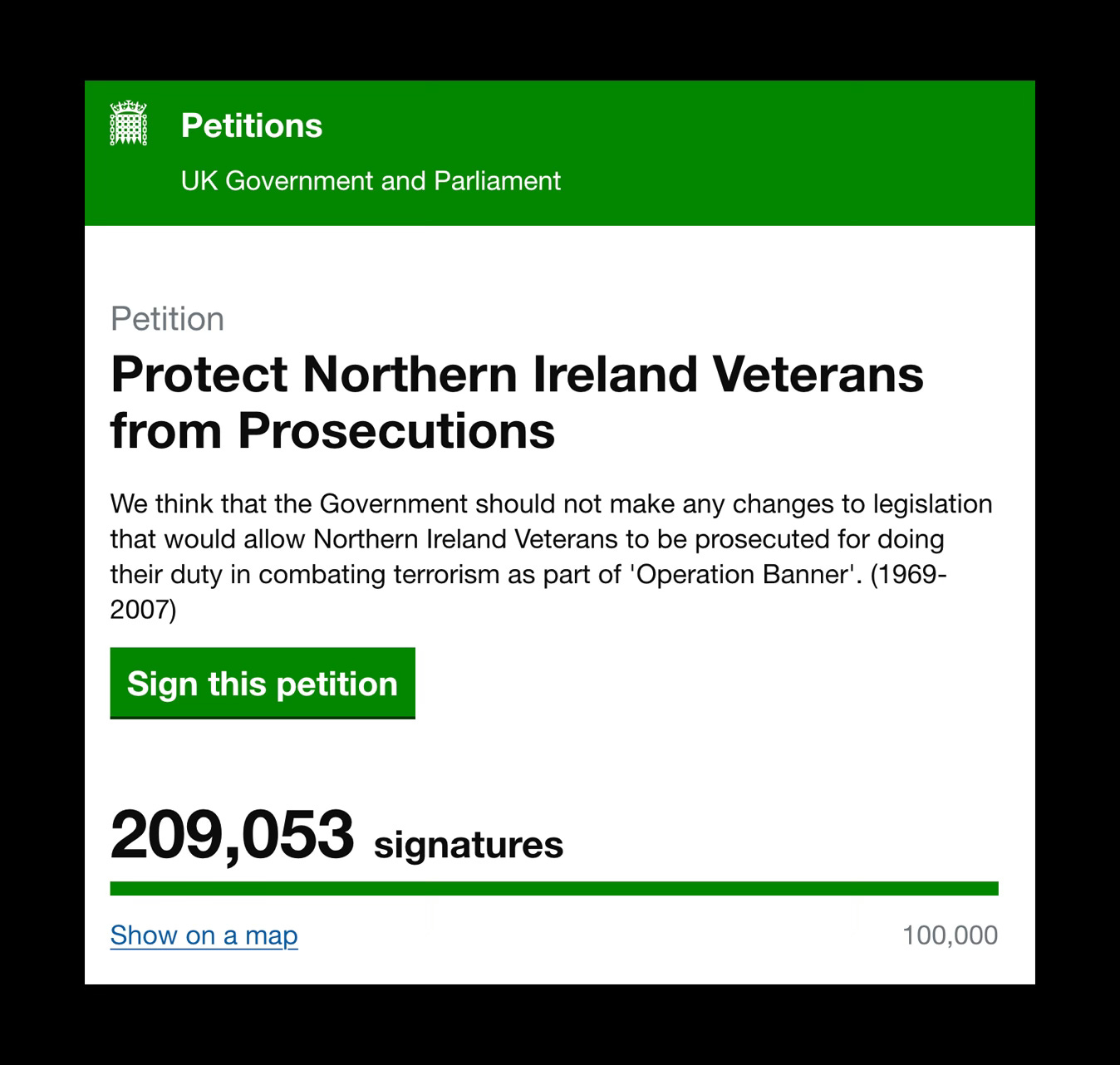

The contrast between the two statements is stark. In July 2025, the Commissioners stood “united in firm support” of a Westminster motion opposing any legislative changes that would expose Northern Ireland veterans to prosecution for carrying out their duty during Operation Banner. Their language was unequivocal: “There can be no moral equivalence between those who served in uniform to uphold peace and the rule of law, and those who sought to destroy it through acts of terrorism.”

The statement called for “clarity, finality, and respect” for veterans—not immunity, but fairness under the law. It warned against retrospective legal action and the retraumatisation of those who had already endured “decades of scrutiny and hardship.”

By September, the tone changed. After the UK and Irish governments announced “The Legacy of the Troubles: A Joint Framework,” the Commissioners welcomed six protections from the Office for Veterans’ Affairs, describing many as measures they had pushed for. They admitted “uncertainty” about the protections’ strength but tried to show a cooperative attitude. Many veterans did not accept this approach.

The Six Protections: A Paper Shield?

The September statement’s embrace of the six protections has drawn sharp criticism. Nick Kiston, Founding Partner at Rose Partners, articulated what many veterans feel: the protections are “too superficial to satisfy the assurances our veterans deserve. They don’t go near the heart of the issue.”

More damning still, Kiston highlighted a fundamental contradiction: “The Irish government made it very clear to their audience that veterans will receive no protections at all. Diametrically opposed to our own government’s claims. Not a good start.”

Guy Wallis, a defence and security consultant, went further, arguing that the six steps “go nowhere near far enough” and contain “enough loopholes to unpick every protection listed.” He cited Lord Dannatt’s BBC Radio 4 interview, in which the former Chief of the General Staff called it “unacceptable that 30, 40, 50 years later former soldiers in their 60s, 70s, and possibly their 80s, are being taken back to events that happened in the 70s.”

The examples Wallis provided are telling: Soldier ‘F’ currently stands trial in Belfast for alleged shootings in 1972, based on statements from 1974 with no new evidence. The 1992 Coalisland incident, involving IRA members killed minutes after attacking a police station, looks set to be reopened despite the absence of new evidence. As Wallis concluded bluntly: “There is no protection for veterans in this mealy-mouthed document!”

There’s also Hilary Benn’s assurances to the families of terrorists that the Loughgall Inquest will be resurrected.

The Pragmatism Defence

James Phillips, Veterans’ Commissioner for Wales, defended the statement’s approach in response to pointed criticism from John Davies, an Army Reserve Officer and Justice of the Peace. Davies accused the Commissioners of “fundamentally misrepresenting what serves veterans’ true interests” and advocating for “dismantling the very Act that provides certainty.”

Phillips’s response was revealing: “I am not supportive of weaponising legal process against veterans, but I am pragmatic about the achievable. Since the NI Legacy Act is being repealed, we need to make sure that protections are in place for veterans who might have to provide evidence. We have to fight for what is achievable rather than pursuing a lost cause.”

This pragmatism, however well-intentioned, lies at the heart of the controversy. Davies’s two-part response exposed the logical inconsistency: “You state that you are collectively concerned about ‘uncertainty’ of the strength of proposed measures, yet advocate for dismantling the very Act that provides certainty. This contradiction undermines your own argument.”

He continued: “Veterans cannot rely on assurances that one party has already begun to qualify,” referencing the Irish Deputy Prime Minister’s remarks that contradict the Framework’s supposed protections. Davies’s conclusion was unsparing: “Replacing concrete protections with aspirational frameworks is not protection — it is exposure to renewed legal jeopardy for doing their duty.”

The Broader Context

The veterans’ frustration extends beyond the immediate legal questions. Simon Parkes, an experienced university chief operating officer and veteran, captured the weariness many feel: “Many of us are tired of the platitudes and the vast sums spent investigating the same issues endlessly whilst our former comrades can’t access mental health services and too many of those currently serving languish in accommodation unsuitable for asylum seekers.”

Roger Lees, who served during Operation Banner, reminded readers of the human cost: over 250,000 personnel served in Northern Ireland, with 1,441 killed, including 722 by paramilitary attacks. His experience of being “spat at” and having “petrol bombs, concrete, and even furniture” thrown at him whilst maintaining professionalism illustrates the impossible circumstances under which these service members operated.

The question Lees raises is pointed: if the government supports compensating victims’ families, must not “the families of fallen servicemen also be afforded the same right”?

A Lost Cause or a Just Cause?

The fundamental disagreement centres on whether defending the Northern Ireland Legacy Act constitutes “pursuing a lost cause,” as Phillips suggested, or standing firm on principle. Davies and others argue that veterans “see through this false choice” and “understand that replacing concrete protections with aspirational frameworks is not protection.”

The Commissioners’ September statement promised to “closely monitor” the introduction of legislation and engage “constructively” on behalf of veterans. But for many in the veteran community, constructive engagement has become indistinguishable from capitulation.

When protections exist only as guidelines rather than guaranteed in legislation, and when one party to the Framework has already signalled a different interpretation, veterans are left exposed.

The Commissioners call for these protections to be “guaranteed in legislation—particularly anonymity for veterans giving evidence.” Yet they simultaneously accept the repeal of an Act that provided precisely such legislative guarantees. This is the contradiction at the heart of their position, and it is one that veterans struggling against lawfare cannot afford to ignore.

The choice: pragmatism or compromise

The 300,000 members of the Armed Forces who served on Operation Banner deserve more than the managed decline of their legal protections. They deserve what the Commissioners promised in July: clarity, finality, and respect for their service. Whether the current approach delivers that remains to be seen, but the veteran community’s response suggests deep scepticism that aspirational frameworks can ever replace concrete statutory protection.

As Davies argued, “This is not a call for immunity from the law, but for fairness under it.”

The question facing the Commissioners—and the government—is whether the current path leads to that fairness, or merely to another generation of elderly veterans dragged through investigations of decades-old incidents with no new evidence and no prospect of closure.

Pragmatism without principle is not compromise. It is surrender.

This is utterly iniquitous.

During the Troubles, the IRA/INLA groups were responsible for 60% of the 3,500 lives lost…….Loyalist groups 30% and the security forces 10%.

As I say in this piece - jwthedilettantepolymath… - who should be investigating and suing who?

Cui bono?

The Labour Party and their activist lawyer and Sinn Fein friends…..that’s who.