Docklands, Doctrine, and the Veteran’s Question

Dean Godson argues the IRA bombing should have drawn a line in the sand. For those who served, it raises a harder question: what happens when the state absorbs violence but scrutinises restraint?

Thirty years after the Docklands bombing, Dean Godson has written a piece that will read, to many veterans and former police officers, like an establishment confirmation of what they have muttered for decades: that the British state decided — quietly, steadily, and with increasing confidence — that the republican movement would not be treated as beyond the pale, but as a necessary component of a political design.

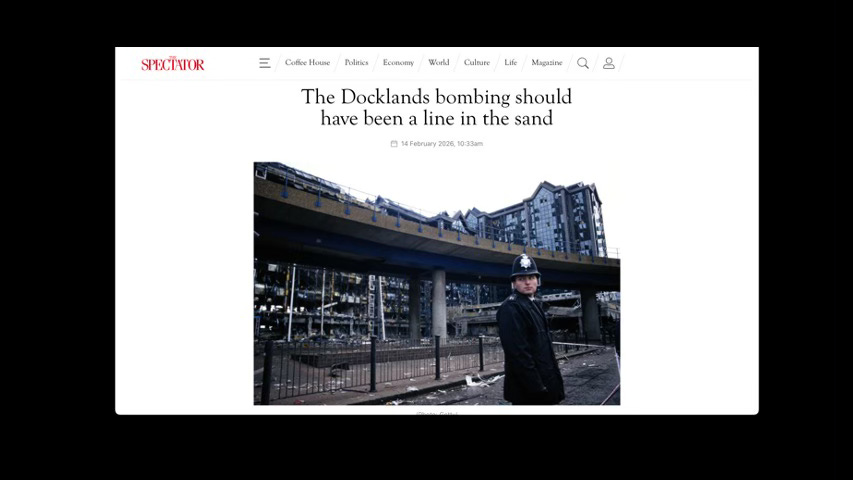

Godson’s argument is straightforward. The Docklands bomb, which ended the 1994 ceasefire and killed two and injured around a hundred, “should have been the moment that placed the Irish Republican movement beyond the pale”. Instead, he suggests, “there is a case for arguing that it actually helped them in the long run.” He writes with personal authority — he was in Canary Wharf when the blast hit — and he is honest about the confusion of the moment: who authorised it, what Adams knew, whether this was a “serious resumption” or a coercive display to “put manners on the Brits.”

Yet the more revealing parts of the essay aren’t the recollections. It’s the description of how the state metabolised the attack. Godson notes that “at no stage did any Conservative minister or permanent official ever suggest that the process could ultimately go ahead without the involvement of Sinn Fein/IRA.” The worst republicans could expect was “a period in the ‘sin bin’ until they restored the ceasefire.” Lord Salisbury (then Cranborne) is quoted as saying Docklands was treated “almost as if it was the cri de coeur of a delinquent teenager rather than a full-scale assault on British democracy.”

This is where veterans will stop reading as historians and start reading as litigants — if not in law, then in the court of moral injury. Because the state can take any strategic decision it likes, but it cannot expect those it deployed to remain psychologically and politically compliant if the logic of that decision is allowed to drift into a habit: violence doesn’t disqualify; it negotiates. It doesn’t foreclose; it accelerates. It doesn’t end the conversation; it forces its terms.

Godson is careful to show that counter-terrorism professionals did not view the renewed campaign as “performative”. John Grieve is invoked, and Operations Airlines and Tinnitus are described as thwarting an IRA capability serious enough that “the entire power supply for London would have gone down.” That is the point. When the men doing the work — intelligence, surveillance, arrests, the quiet routines that prevent horror — judge an adversary by capability and intent, while the political class judges by process and destination, you get two truths running side by side. One is operational. The other is political. The trouble is that only one of them comes with prosecutions attached, and it is rarely the political one.

The veteran’s grievance is not that peace was attempted. It is that the price of peace has been unevenly distributed, and then sanitised with the language of virtue. Soldiers and police were held to law and restraint — rightly, as servants of a democratic state. But when restraint becomes not merely a discipline but an identity, and when that identity is later treated as retrospective liability, you have created a trap: you demanded restraint because you were civilised, and now you are investigated because you were there. Meanwhile, Godson reminds us that the Docklands conspirators “got out of prison early under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement” and that one bomber received a Royal Prerogative of Mercy after serving “just two years”.

The point here is not to reopen old arguments about prisoner release. Those arrangements were part of the bargain; the country made it, and history has moved on. The point is what the bargain taught the state to prioritise. Godson writes the quiet line that veterans will find least easy to swallow: “sustaining the Sinn Fein/IRA leadership had become one of the highest goals of state policy.” If that is true — and he presents it as an established fact of the late 1990s — then the moral centre of gravity shifted. The aim was no longer simply to stop violence, but to stabilise a particular leadership that had been complicit in it, because the leadership was now a mechanism for managing it.

That is exactly the sort of calculation a state will make. States are not churches. They do not do penitence. They do order. The difficulty is that the state then asks its servants — especially those who served in the most morally complex theatre on these islands since the war — to treat that calculation as a moral story in which the only legitimate emotion is gratitude. Veterans are expected to be grateful for peace, full stop. They are told that to question the logic is to question peace itself. It is an old trick: conflate an objection to the method with an objection to the outcome. It saves time in Parliament and in polite society, but it doesn’t restore trust.

Godson also suggests something else, and it may be the most strategically important element of the article. He argues that an “international ideology of Northern Ireland” emerged, with Jonathan Powell as a prominent exponent, and that its lessons are now “imbibed across the world in conflict zones, most notably in Gaza.” One of the “takeaways”, as he reports it, is: don’t demand decommissioning up-front; and when you do demand it, avoid public humiliation (“no Spielbergs”).

Veterans will read that and think: so Northern Ireland did not merely end; it became doctrine. And doctrine travels. Which raises a modern problem: if the lesson exported is that insurgent violence must be accommodated to secure political movement, what lesson is imported back into our own politics? We are already seeing it in miniature. Legality becomes the whole argument; judgment is treated as indecent; procedure replaces discernment; the state’s first instinct is to manage the risk of destabilising the “process”, rather than to defend the moral legitimacy of those it asked to enforce order.

This matters because the legacy debate is not chiefly about the past. It is about whether the state can still credibly ask young men and women to take on morally ambiguous work under legal restraint, while offering them neither legal finality nor institutional loyalty afterwards. If you want disciplined restraint in the next grey-zone theatre, you cannot build a system that teaches the soldier he will be punished for restraint and abandoned for obedience. A state that cannot draw a line for its servants will eventually find its servants drawing a line against the state.

Godson’s piece is meant, in part, as a critique: Docklands should have been a line in the sand. Veterans will nod — and then add, quietly, that the line they are waiting for now is not about whether talks happened, or whether peace was worth it. It is simpler. It is about whether the state will finally stop treating those it deployed as the disposable residue of a political success story.

If the Northern Ireland settlement required hard compromises, so be it. But a serious country does not allow those compromises to harden into a permanent asymmetry: indulgence for those who broke the law, suspicion for those who upheld it. Godson has, perhaps unintentionally, written a reminder of the veteran’s question—a question the political class keeps trying to paper over with warm words.

It isn’t a warm-words problem. It is a finality problem.

Way back in 1972, when I was a captain in the Belfast reserve battalion serving the start of a 2-year tour in Northern Ireland Edward Heath appointed William Whitelaw as Secretary as State for Northern Ireland. He was the first. Within a year of his appointment I was beginning to think I should quit the Army. Even back then it was apparent to us soldiers that our politicians didn't have our backs. The squaddies didn't give Whitelaw the nickname Willie Whitewash for nothing. Fortunately for me I went off to Hereford and passed Selection instead off prolonging the futility of that long tour in Belfast and the subsequent years when my friends were hounded through the courts for their brave work with the MRF back then.

I reckon “a necessary component of a political design” can also be, in certain circumstances, appeasement – though the terminology and euphemisms employed depend on one’s point of view. Seems to me that appeasement, which can be a process or a single act, has been in the British establishment’s DNA since the *Suez debacle in 1956, such was the embarrassment. (The commencement of the highly successful Malayan Emergency preceded Suez, and the especially successful Dhofar War was not, strictly speaking, a British conflict. The conclusion of other conflicts, which witnessed acts of military prowess and individual courage, mostly ended messily, politically speaking, apart from the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, and the Falklands, thanks to a magnificent all-arms effort and an exceptional prime minister.)

In respect of the Northern Ireland Troubles, I think a long-sustained military effort assisted by a high-octane boost from SF (Op Banner) was squandered by wilful political appeasement (The Good Friday Agreement), which resulted in lenience to terrorists and the persecution of veterans. It has achieved nothing but offering leverage for further concessions. The new Troubles Bill is simply a continuation of appeasement by the British government to Dublin and Sinn Fein. Gaza will see the same pattern if Jonathan Powell has anything to do with it. Indeed, it already has. The nation-state means little to cold globalist ideologues and its veterans mean even less. Gangster-bosses become the first-call as interlocutors with whom to broker a deal. Legal process is built around appeasement.

Terrorism, and its derivatives, work – when dealing with western democracies. Indiscriminate murder versus the Yellow Card mindset and Liberal timidity. I had no problem with my tours in NI from 1972-77 except the sixth and last one when I felt that eventual capitulation was inevitable if not deliberate.

*It is a matter of record that President Eisenhower came to regret his decision not to support Britain over Suez.